Prevention is always better than cure. That's why we regularly work with landholders and Local Land Services (LLS) to fence off the creeks and establish off-stream watering points. These help to limit the damage caused by horses and cattle that often get into the delicate creek area. In more extreme cases, to secure the banks without affecting the nearby zones, we have to use soft-engineering techniques like brushing or installing pile fields.

Since 2008, Council has restored over 50km of streambank in the Tuggerah Lakes catchment.

Artificial Stormwater Treatment

Stormwater is the rainwater that runs off hard surfaces and through the drainage system, and later enters into nearby streams, creeks, rivers, estuaries and finally – the ocean. As stormwater runs freely, it picks up various pollutants, including nutrients, sediment, litter, green waste and debris. They are the largest source of pollution impacting the overall health of our estuary.

Fertilisers and various household chemicals are a major offender to the cleanliness of our waterways. The research shows that pollution loads from the urban environment, containing phosphorus, nitrogen and suspended solids, are usually between 150% and 400% above natural levels. They are highly reactive, and upon entering the waterways, they get quickly taken up by algae and phytoplankton, resulting in algal blooms and degradation of the bed sediment.

In the Tuggerah Lakes catchment, Council manages a suite of over 300 stormwater treatment devices: from gross pollutant traps to constructed wetlands and saltmarsh swales. Together, they work to trap or remove a large chunk of the pollution material, so that it does not make its way to the estuary. Each year, around 1000 tonnes of various pollutants are caught and diverted to landfill, making our waterways cleaner – and healthier.

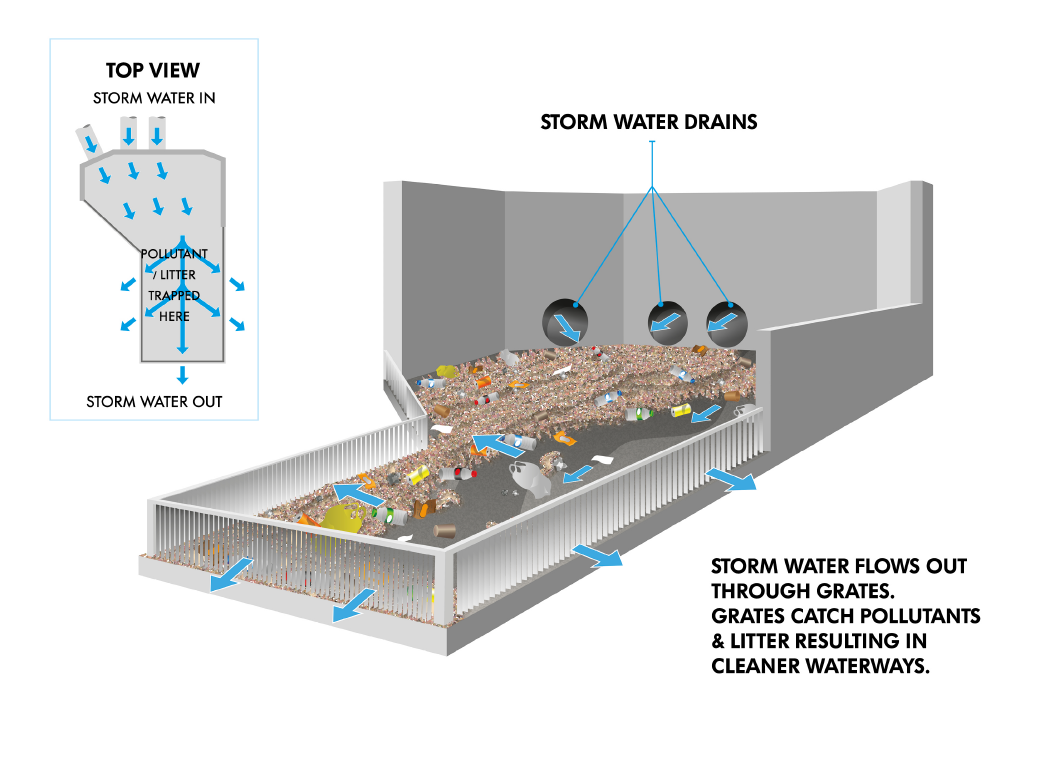

Above Ground Gross Pollutant Traps

These smart devices help to catch stormwater pollution – so litter, debris, grass clippings and coarse sediment – before it even enters our waterways. Called Above Ground Gross Pollutant Traps (or dry sumps, as they stand above the water level), they work targeting solids greater than five millimetres. Dissolved pollutants and fine materials may still pass through the filters. Dry sump GPTs allow stormwater to flow through a chamber, trapping large pollutants in a grid-like barrier that lets the water continue further to the lakes. They are easy to clean and also allow the waste to stay dry, which prevents it from breaking down and entering the waterways. As a whole system, these machines are far more efficient and easier to maintain than other popular options, such as drainage pipe nets or filter bags.

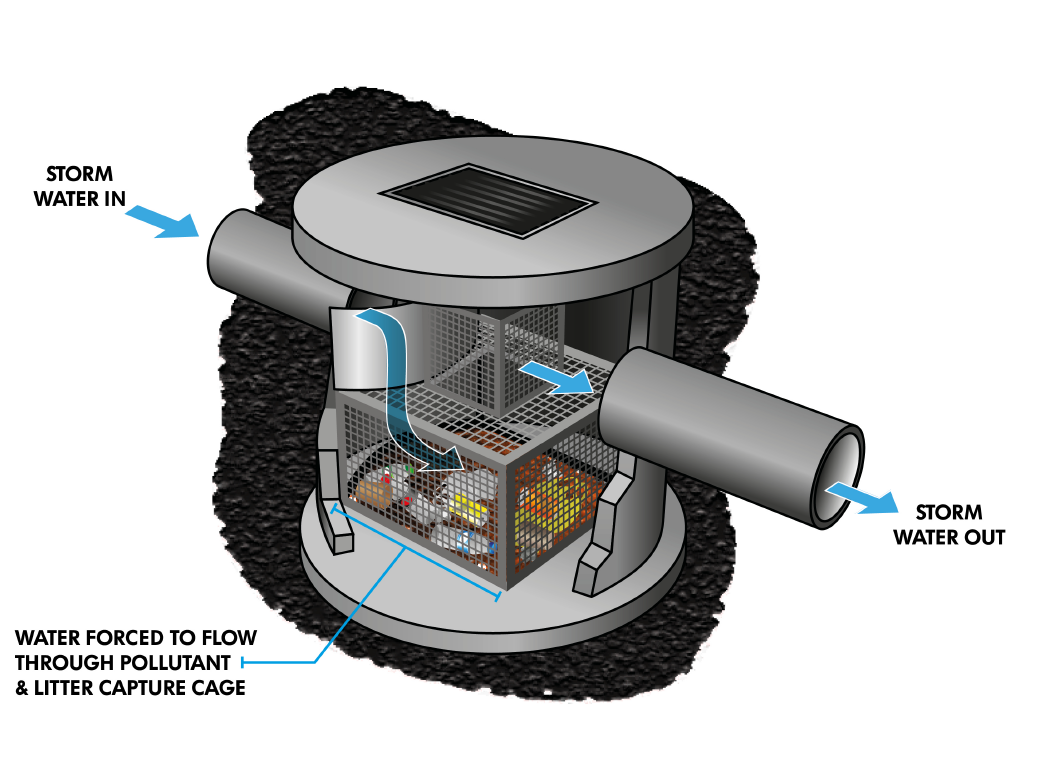

Below Ground Gross Pollutant Traps

Below Ground GPTs form another category of water pollution traps. Also known as wet sumps, when installed, these devices stay permanently submerged. They work similarly to dry sumps by removing large, non-biodegradable pollutants. However, wet sump GPTs are more complicated to build and more expensive to operate. As they are placed underwater, they are also harder to clean and require frequent upkeep. Their primary benefit is aesthetic – they are hidden from the public view while still protecting Tuggerah Lakes from impurities.

Constructed Wetlands

Constructed wetlands are engineered ecosystems designed to clean all wastewater, including stormwater. They consist of shallow, densely planted artificial ponds that help to filter water through physical and biological processes. In other words, artificial wetlands use plants and naturally-occurring microorganisms to reduce or remove nutrients, pathogens and sediments. Whereas the upstream GPTs remove some of the litter and coarse material, the wetlands' ponds and plants are able to filter out finer pollutants and take up excess nutrients. In addition to their water-cleaning benefits, they also provide an attractive landscape feature and a local habitat for frogs and birds.

In a bid to consistently improve our water management systems, we are currently undertaking an in-depth analysis of the performance of constructed wetlands to determine their optimum maintenance schedule.

Swale Pathways

Swales are shallow, broad and vegetated channels that can be either naturally formed or purpose-built. They consist of growing grasses and other plants. When stormwater passes through them, coarser sediments and nutrients infiltrate into the subsoil once the flow of water has slowed, which prevents the pollutants from entering Tuggerah Lakes. The remaining, more delicate material binds to the vegetation.

Typically, constructed swales use native, freshwater wetland plants. However, Council has recently built several swales using salt-tolerant native species, which also help to treat stormwater in this highly dynamic area.

Healthy Wetlands

Wetlands play an essential role in the landscape and ecosystem of Australia. Globally, they cover approximately six to nine per cent of the Earth’s surface and contain about 35 per cent of global terrestrial carbon. They function as carbon sinks that provide a range of ecosystem services that humans rely on – purifying water, regulating water flows, and protecting the coast and its biodiversity. Typical wetland vegetation includes reeds, rushes, shrubs and trees, which trap pollutants before they can reach our waterways.

In their natural state, wetlands can be either permanently or seasonally submerged. Their versatile nature means that the plants growing there are well-adapted to the extremes, and can tolerate waterlogged soils or periods of dryness while still providing shelter and food for many lands and diverse aquatic animals.

Historically, wetlands were cleared and filled to make way for building cities and expanding local businesses. Catchment pollution and the poor use of land have harmed these valuable areas, resulting in water sedimentation, weed growth and algal blooms. Now, as we understand the significance of these wetlands more, we need to protect them at all costs. Of course, high-density urban development makes it more difficult, as it tends to send more water and pollution into the catchment. Yet, we know that everyone benefits from the smart management of our waterways, and the maintenance and restoration of wetlands. They contribute to the productivity of farming and fishing industries, and help to protect the health of our lakes.

Preserving wetlands means keeping water cycles, water volumes and water quality as close to a natural state as possible. As a goal, we should stop treating natural wetlands as our filters, but work towards improving the quality of water before it reaches their vegetation so that these green patches of nearshore zones stay healthy and thrive.

Since 2008, Council has protected and rehabilitated over 375ha of natural wetlands in the Tuggerah Lakes catchment.

Healthy Saltmarsh

Saltmarsh is the mosaic of coastal wetland ecosystems that occupy areas of low energy, minimal wave action and intermittent tidal inundation. On the Central Coast, they spread over the foreshores of Tuggerah Lakes and other estuaries. Saltmarshes consist of plants such as reeds, grasses, succulents and shrubs, which are well adapted to growing in brackish water – a mix of salt and freshwater – and muddy soil. Saltmarsh areas act as a buffer between the land and the ocean, protecting shores from erosion and filtering out sediment and organic matter before they enter the water. Their activity helps to keep our lakes clean and healthy, while also providing nutrients and shelter for many animals and birds.

Once considered wastelands, saltmarsh areas are now known to be extraordinarily diverse and biologically productive. Like rainforests and coral reefs, they provide an essential habitat for many animals, particularly wading birds. Many fly long distances to feed and breed in the long stretches of saltmarsh around Tuggerah Lakes. As saltmarsh sediments are rich in organic matter, they create a nutritious environment for many invertebrates. Mussels, oysters and crabs thrive in the mud, attracting wading birds and fish looking for a meal.

Protecting and restoring our saltmarshes is extremely important to the long-term health of our lakes. We estimate that locally, 80 per cent of these precious ecosystems have already been lost. In places where saltmarsh still exists, Council has worked hard on ways to protect and restore it. The smartest policies of saltmarsh restoration often translate into recreating the right conditions for it to grow and thrive.

Since 2008, Council has protected and rehabilitated over 30ha of native saltmarsh and has reconstructed a further 2.7ha in the Tuggerah Lakes catchment

Well-balanced Foreshores

The foreshore is a zone between high and low water, or between the ocean and the developed land. In Tuggerah Lakes, it provides a recreational space for our community, while also serving an important ecological function for the whole estuary.

To ensure the long-term sustainability of our lakes, Council needs to make sure that these competing uses are well-balanced. We want to achieve this in two ways. Firstly, the foreshore space has to keep its function as the local hub of outdoor activity, providing a range of attractions for our community, as well as supporting active lifestyles and sustainable transport. Yet, secondly, we also have to ‘tread lightly’ and protect our estuary’s ecological balance.

Central Coast Council manages a network of broad and accessible shared pathways, which include a scenic, 29-kilometre-long ride around Tuggerah Lakes. We have installed educational signage along the path, where fitness stations, playgrounds, barbeques and rest points abound. In the future, there is a plan to expand these amenities to make our lakes a perfect recreation spot for the local community and visitors.

The 2006 Tuggerah Lakes Estuary Management Plan (TLEMP) supports both the sustainable development of the area and its socio-economic goals. Again, there is a need for a rational and pragmatic consensus here. Our action plan specifies how we interact with and use the estuary. Tuggerah Lakes offers a number of significant opportunities relating to its tourist and recreational value, and it also has an excellent commercial fishery potential. The main objective of our strategy is to facilitate a smart and gentle use of the lakes that is not detrimental, but rather, beneficial to the health of the estuary.

Wrack Management

Seagrass wrack or seaweed is a common sight around much of the Australian coastline. In estuaries, it typically consists of the detached seagrass leaves floating around or piling up on the beach. As an organic material, wrack serves an essential ecological function for the estuary.

However, it is often also the leading source of bad smells and unpleasant views on our beaches. Since we want to make sure our community enjoys Tuggerah Lakes to the fullest, we are committed to the regular collection of seagrass wrack and floating macroalgae to improve the recreational value of Tuggerah Lakes.

This annual wrack management can also assist with nearshore mixing, which is the transportation and dispersion of pollutants and nutrients within the estuary, and which supports the circulation of these elements to enhance the quality of our water.

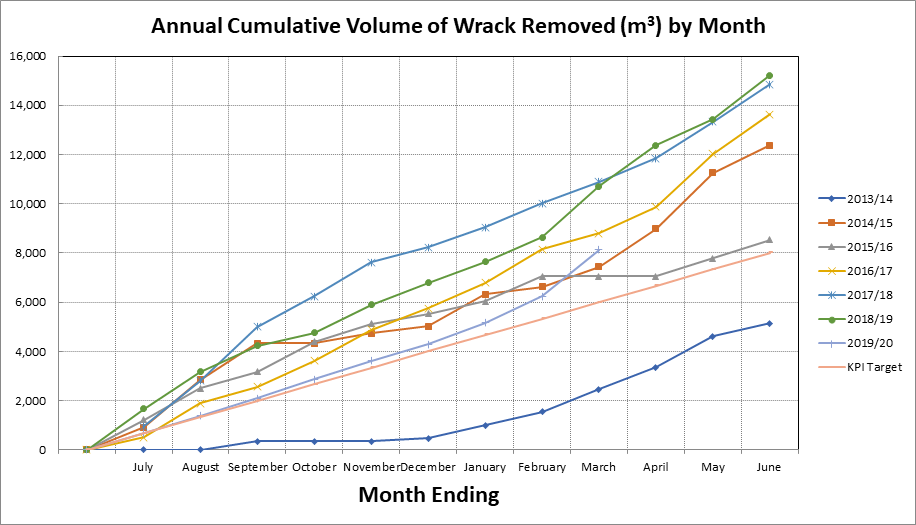

Wrack Collection Statistics

Wrack collection is prioritised according to which area around the lakes needs it the most. These competing demands take into consideration levels of public use, benefits for the environmental health of the lakes, as well as accessibility and seasonal patterns of wrack accumulation throughout the year.

The current program has been developed in consultation with scientists from the NSW Government to meet the objectives of the Tuggerah Lakes Estuary Management Plan. Some areas of the lakes have their own delegated 'wrack reserves', which allow wrack to stay a part of the estuary's natural cycle.

Since 2014, Council has increased the annual wrack collection targets from 4000 to 10,000 cubic metres. We currently manage over 70km of the foreshore, which involves a sustained effort and investment throughout the year.

Each year, we manage to exceed our wrack collection targets. For example, in 2016/2017, Council removed 13,642 cubic metres of wrack from various nearshore areas in Tuggerah Lakes.

Through Research to Better Management

It is a known fact that knowledge stirs innovation and improves lives. The Council's local scientists regularly collaborate with industry experts to further our understanding of the estuary. To yield the best results, we want to adapt our programs to the most pressing needs.

Here are some examples of the current research in and around our catchment:

- The Tuggerah Lakes catchment, hydrodynamic and ecological response models;

- The Tuggerah Lakes wrack model and seasonal wrack collection strategy;

- Berkeley Vale nearshore water quality study;

- The estuary's water quality monitoring program;

- The freshwater ecological health monitoring program;

Future projects around the lakes will include a seahorse abundance and diversity study, stormwater improvement device study and The Entrance decision support tools. We strive to incorporate the findings from these projects into the future Coastal Management Program.