Drought and Rain

The dynamic nature of the Australian coast means that long-lasting droughts can be followed by heavy rains and flooding. These fluctuations are natural as they bring the environment back to life, but they can also pose considerable risk to floodplain-inhabiting communities. There are a few different flood categories, which take into consideration their type, size and duration:

- Catchment flooding is caused by prolonged or intense rainfall, for example severe thunderstorms and extratropical cyclones called east coast lows (ECLs). The massive amounts of water running off catchments can lead to:

- Banks of creeks and rivers breaking, as has happened with the Hawkesbury River, Erina Creek, Narara Creek, Ourimbah Creek, Wyong River and many others;

- Filling of coastal lakes and lagoons, which has occurred with Tuggerah Lakes, Wamberal Lagoon, Terrigal Lagoon, Avoca Lake, Cockrone Lagoon and Pearl Beach Lagoon;

- Overland flow across ordinarily dry land in both urban and rural areas on its way to waterways.

- Coastal flooding occurs due to tidal- or storm-driven coastal events, including storm surges and wind-induced waves in coastal waterways. Some known examples where this type of flood occurs:

- Brisbane Water and the lower reaches of Narara Creek and Erina Creek;

- Hawkesbury River;

- The coastal beachfront.

- A combination of both catchment and coastal flooding in the lower portions of coastal waterways can happen after one or a series of storms. There are a few factors that influence which of these two sources of flooding is dominant: the location and configuration between the catchment, floodplain and waterways, as well as the specifics of storm cells (air masses that contain updrafts and downdrafts). If there is a high tide or a storm happening at the ocean entrance at the time of rainfall, the lake flood level will be even higher.

Flooding in Tuggerah Lakes

Central Coast Council has reliable flood records for Tuggerah Lakes that go back over 90 years. Since the documentation started, we have experienced 12 floods reaching a height of 1.5m above the Australian Height Datum (AHD or mAHD for metres above the Australian Height Datum) or more. The highest flood recorded for the lakes was 2.1 mAHD in June 1949. The most recent flooding event happened in February 2020 and reached 1.67 mAHD, becoming the 6th highest on record. It is followed closely by the ‘Pasha Bulker’ flood from June 2007 at 1.65 mAHD. The February 1990 and March 1977 floods also reached 1.6 mAHD.

| Date | Approximate Peak Lake Level (mAHD) |

| February 2020 | 1.67 |

| June 2007 | 1.65 |

| February 1990 | 1.6 |

| March 1977 | 1.6 |

| May 1964 | 1.9 |

| 1963 | 1.5 |

| 1953 | 1.5 |

| June 1949 | 2.1 |

| Easter 1946 | 1.9 |

| 1941 | 1.5 |

| 1931 | 1.8 |

| 1927 | 1.8 |

100-Year Flood

A 100-year flood (also called a '1-in-100-year flood') is a flood height that has a 1 in 100 chance of being equalled or exceeded in any given year.

For Tuggerah Lakes, this '1-in-100-year flood' is estimated at 2.2m, which is just a bit higher than the level reached in 1949. Another estimate, the Probable Maximum Flood (PMF) refers to the largest flood that could conceivably occur in present climatic conditions. For our region, this is estimated at 2.7m.

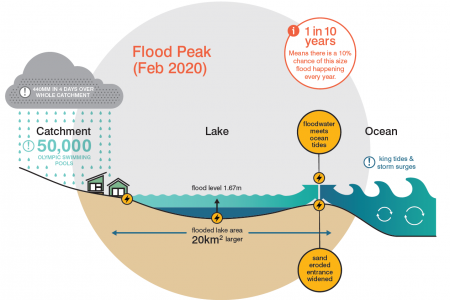

The February 2020 and June 2007 floods were both 1-in-10-year Average Recurrence Interval floods. The Bureau of Meteorology classifies them as minor events. Typically, each year, there is a 10 per cent chance of a flood this size. Moderate floods are higher than 1.8m, and there have only been five of these in the past 90 years. The most recent one occurred in May 1964 and reached 1.9m. Luckily, since the 1930s, we have not experienced a major flood event that would reach 2.2m (or higher).

When A Flood Comes

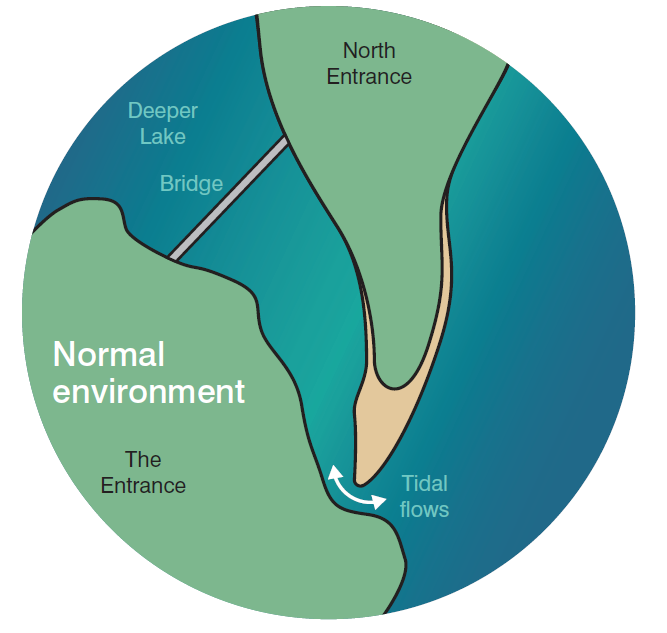

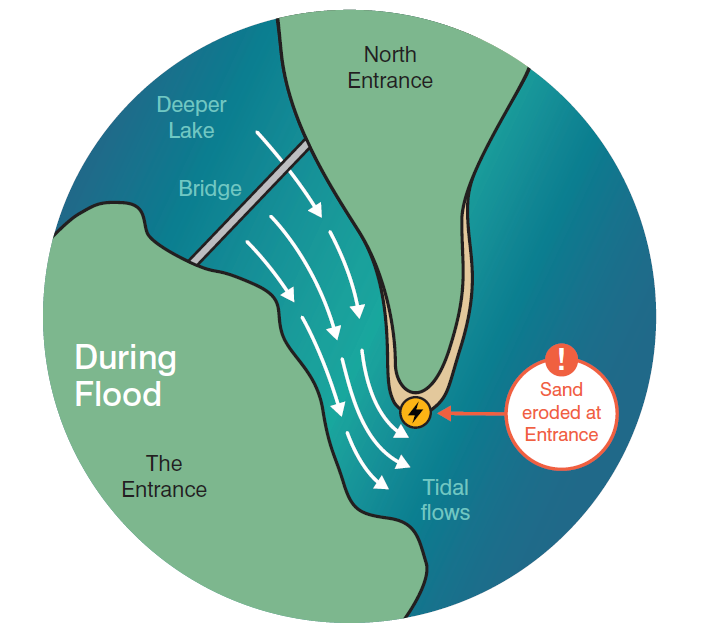

When Tuggerah Lakes floods, the rivers and streams carry vast amounts of water to the estuary over a relatively short time. The lakes and surrounding floodplains fill with water from the streamflows, stormwater and rain. As floodwaters rise, the water flowing out of the lake at each low tide becomes faster and more powerful. It washes away sand at the beach berm and makes the channel wider.

The floodwater can continue to flow out of the lakes for several days. For it to drain away more quickly, the ocean's water level must be lower than the lake's. Otherwise, the water stays where it is. Weather conditions during the flood also influence how soon the draining away can happen. For example, when a flood coincides with a coastal storm, an east coast low or a king tide, the water can flow back into the lake during low tide, and the floodwater recedes more slowly.

Large waves and storm surges move the sand offshore, but it is mostly retained in the coastal sediment compartment not far from the lakes' entrance. Even though it seems counter-intuitive, the sand offers welcomed protection from coastal storms and coastal erosion, which can both be severe at times.

Once the floodwaters recede, the channel slowly fills in and closes over again within months, depending on the follow-up rainfall. During this time, the entrance berm grows from the northern shoreline in a southerly direction, eventually reaching the rock shelf again. This process can slowly constrict the tidal exchange between the lake and the ocean, bringing it back to normal conditions.

During a series of storms that savaged the coast in February 2020, the Central Coast area received around 440mm of rain over just four days. This amount of water is the equivalent of 500 Olympic swimming pools being poured into the Tuggerah Lakes catchment alone, and would typically equal the Australian rainfall average for nearly 12 months. These storms caused the water surface to rise from 80km2 to around 100km2 again, increasing the lakes’ water level from 0.25 mAHD to 1.67 mAHD. The floodwater took a long time to drain away and was affected by the oceanic conditions.

Flood Safety Preparation

The growing population of the Tuggerah Lakes' catchment has always lived with the risk of flooding. To help manage the flood situation, Council applies strict development controls for all new housing and infrastructure projects built in low-lying, flood-prone areas. For example, all the latest developments need to have a Minimum Habitable Floor Level of 2.7m above sea level. This means that the new sites must be constructed to this height. Similar building restrictions have been in place for over 40 years.

The Minimum Habitable Floor Level of 2.7m is set 0.5m above the 1-in 100-year flood level, which means that – for safety reasons – it is over 1m higher than the February 2020 peak flood height. It is also the same height as the Probable Maximum Flood in Tuggerah Lakes.

Non-habitable areas within a house such as garages can be built at lower levels. When buying a house in the flood-prone area, it is recommended to check all these necessary safety measures and see whether they comply with Council's regulations.

Managing Flood Risk

To provide our community with the most accurate flood information, Council undertakes several flood studies and develops flood risk management plans for the Central Coast. In these documents, we identify flood-prone areas and investigate how to best prepare for a flood event so that there is minimal damage to the properties and no risk to lives.

If you are a resident of the Central Coast, find out more about your flood risk on Central Coast Council's website. For more information on how to prepare for a flood and for live updates on flood incidents, visit the Central Coast Council Disaster Dashboard.